|

Counterpoise Definition

“Counterpoise” has been used by radio amateurs since the very

beginning of our hobby. When operators couldn’t

get a good earth ground, perhaps because they were on the second floor of a

house, the common suggestion was to “use a counterpoise wire”. A grid of conductors parallel to a dipole, laid on earth or suspended above

earth, is often referred to as a counterpoise. After all, the word “radial”

hardly fits a group of parallel wires with no real connection to the antenna’s

feed terminal. Counterpoise, in popular Ham radio conversation, has always

described a conductor or group of conductors serving as an RF ground.

Counterpoise definitions can be found in

dictionaries. Here is the definition of “counterpoise” appearing in the Communications Standard

Dictionary:

A

counterpoise is a conductor or system of conductors used

an earth or ground substitute in antenna systems. When we look at how

the word has been commonly used, we see general use and dictionary

definition agrees.

Model and Measurement Anomalies

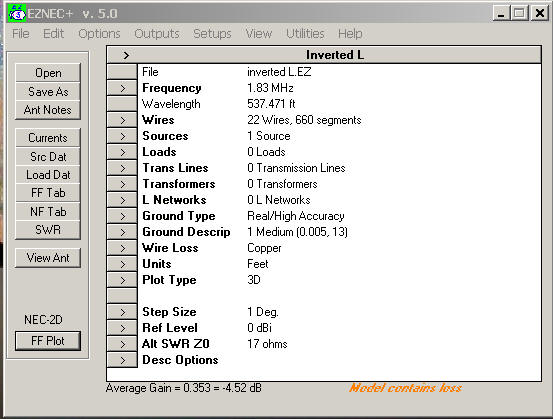

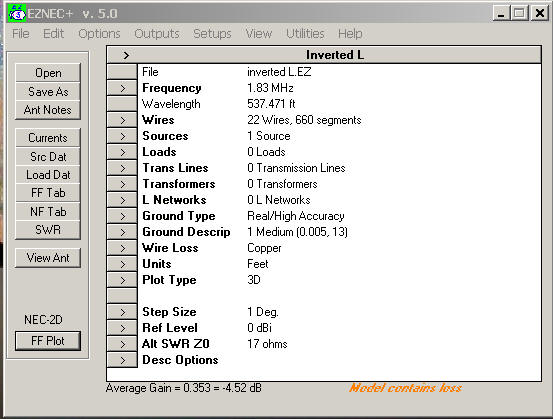

Average gain can be a useful tool in EZNEC, as can maximum or peak gain. This

is how it is displayed:

In this case, using a 3D plot, we see Average

Gain appear at the very bottom.

Average gain is .353, which translates to 35.3% radiation efficiency.

Also displayed is -4.52 dB, which is the total power loss of the entire

system.

Average gain is also an indicator of improper modeling if average gain exceeds 1.00, or is

unreasonably high.

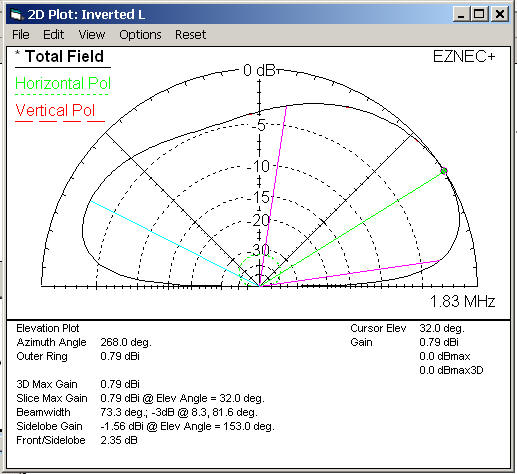

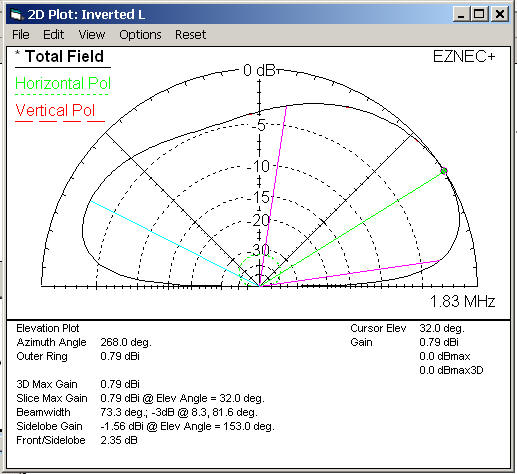

Peak gain or maximum gain is another common performance indicator. It is

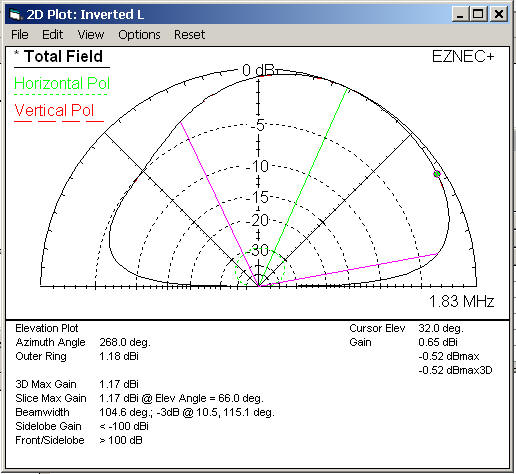

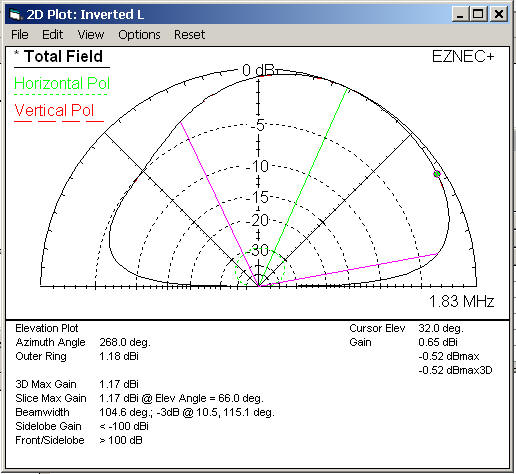

displayed in the pattern plot:

In this case we have a 3D maximum gain of .79 dBi at 32 degrees elevation

The counterpoise is made much smaller, and this appears to have slightly

better efficiency and average gain, but it is misleading.

By looking at pattern we see significant reduction in the left area of

pattern, and less gain at the lower, former maximum gain, angle. This is still a

useful comparison for peak radiation at long distances.

Remember patterns are plotted at a very large distance over flat

earth. This makes groundwave look like zero, and makes an already abused

parameter, take off angle (TOA), even less useful.

In a real vertical antenna less than ~3/4 wave tall, field does NOT

reach zero near the antenna at low angles.

|

An Inverted L, or any antenna with susceptibility to horizontal polarization, can give misleading ground efficiency results with compact or non-symmetrical counterpoises.

A full counterpoise below the flattop suppresses horizontally polarized

radiation. By removing or reducing ground reflection below the horizontal

antenna section, the low radiation angle vertically polarized Inverted L antenna

is moved toward “low dipole mode”. If we look at peak or average gain when

changing to a counterpoise or ground system that no longer suppresses horizontal

radiation, we can see what appear to be improvements. These peak

gain or efficiency improvements come from increased

horizontal radiation component, rather than improved vertically polarized field strength.

After modeling many systems, I’ve concluded the best antenna for comparing

ground systems is a top loaded vertical (for very short radiators), T vertical,

or full-size λ/4 vertical for taller

radiators. This keeps high angle “dipole mode” out of maximum gain or efficiency reports, especially when

doing earth-height efficiency sensitivity reports or evaluations. Otherwise,

if we use an antenna susceptible to horizontally polarized radiation, we must

compare absolute gain at low angles in all important directions.

feed lines and matching systems should be included in all models. It is

possible to “build” antennas that work very well in models, but rarely function

like the model in real life. Some well-known authors, including one who

pioneered early amateur modeling programs, have “invented” antennas that never

achieve predicted results because they never included feed lines, or tested for

sensitivity to feed line or matching system balance, or feed line or matching

system loss. This applies across the board to all antenna models, both receiving

and transmitting.

Those around me who do the most work and spend the most money, and have the

poorest results, mostly willy-nilly change to a better system without thinking

through changes, let alone documenting field strength changes. Every time one local amateur

changes antennas, the new antenna is always “killer”. He has gone from so many

“killer” to even more “killer” antennas, yet skimmer shows him the same

level as any other reasonable station from around here.

Another common, but low value, comparison method is contest results,

or DXCC totals. Scores trend

upward over time as people improve things. This is true for both skill,

increased activity, and

improved equipment. There are multiple causes at both ends

influencing results, including noise level, activity, equipment, human factors,

propagation, how enthusiastic we are, and even luck or fortune. We tend to

operate more when we “feel good” about something new, and operating more always

improves results.

Finally, false claims

and junk science universally depend on test errors, operator “feelings”, or

signal reports to support radial departures from good methods and science. It is not all that difficult to install reliable reference antennas with proper

construction and make A-B comparisons. The burden falls upon inventors of exceptional claims to provide

reasonable comparisons with systems known to work to some standard, not on

others to disprove them.

I can’t imagine changing antennas here without any idea if the previous

antenna was installed properly, or how the new antenna compared. I fell into

this trap several times before in my life, and it slows my personal progress. I

certainly have learned my lesson over the years. If I want to know something, I

directly measure, or measure as directly as possible, what I want

to know.

Counterpoise LF, HF, and MF Applications

Radials

Radial or buried screen systems, in direct soil contact, are generally

preferred in permanent installations. On lower frequencies, buried systems work just as well as

elevated systems. They also have much wider useable frequency range than

counterpoise systems. The broad frequency response of buried or ground-contact

systems not only helps cover wide radio frequency ranges, buried or ground

contact systems also offer significant lightning and electrical safety

advantages over ground-isolated systems. Buried or earth contact systems offer

grounding from dc to very high frequencies.

There is a popular myth among Hams and technical writers that USA Standard Broadcast systems require 120

radials. From that myth, people assume a “perfect radial ground system” requires 120

radials, each 1/4 wavelength long. This leads some to write articles or offer

advice stating peak efficiency requires 120 radials. The FCC actually says nothing of

the sort. 120 radials is not, and never was, considered a

minimum radial count for a “perfect ground” system.

If at least 90 radials

λ/4 are used, the FCC does not require

complex ground system efficiency proofs.

Ninety radials is the threshold to avoid spending money proving the

ground system works, even 90 radials is not a minimum requirement. Stations are free to use

fewer radials, and often do use fewer radials, provided they prove adequate antenna system

efficiency.

Exact FCC text is:

(4) At the present development of

the art, it is considered that where a vertical radiator is

employed with its base on the ground, the ground system should

consist of buried radial wires at least one-fourth wave length

long. There should be as many of these radials evenly spaced as

practicable and in no event less than 90. (120 radials of 0.35

to 0.4 of a wave length in length and spaced 3° is considered an

excellent ground system and in case of high base voltage, a base

screen of suitable dimensions should be employed.)

(5) In case

it is contended that the required antenna efficiency can be

obtained with an antenna of height or ground system less than

the minimum specified, a complete field strength survey must be

supplied to the Commission showing that the field strength at a

mile without absorption fulfills the minimum requirements. (See

§73.186.) This field survey must be made by a qualified engineer

using equipment of acceptable accuracy.

|

|

We see the FCC never said 120 radials make a perfect system, or even that 120

radials are the minimum requirement. The FCC said 90 radials will prevent having

to prove efficiency, and 120 radials

.35-.4 wavelengths, plus a base area screen if voltage is high, is considered

“excellent ground system” effort.

Reinvention of the FCC section above is commonly used to exaggerate

differences between conventional and

elevated systems. The typical exaggeration is something to the effect

of, “four elevated radials are equivalent to 120-radials on the ground”.

Such statements are very misleading. They imply or reinforce myths that 120

ground radials are required for a “perfect” ground. 120-radials were never established as a minimal

“perfect ground”. 120 radials are not even an “FCC mandated ground”.

Still, practical radial systems can be large. Without question, earth-contact

radial systems require more

wire than proper elevated systems for the same single-band RF performance. Note

this generalization is for a single band system, and also does not consider safety or

lightning mitigation. At my location a 7 MHz 1/4λ

vertical reaches the flat portion of efficiency improvement with

approximately 20-25 buried radials. That is still a

great deal of wire (~600 feet), although nowhere near the exaggerated 120-radial

requirement implies (3,600 feet). At my location, 12-15 buried radials (about

400 feet of wire) equals four elevated resonant radials (about 120 feet of wire)

when .05

wavelengths high on 40 meters. Wire savings is very close to 4:1, rather than

the falsely implied 30:1.

Field strength of my 160-meter 1/4λ

verticals, at my present location, stopped improving with around thirty-five ~1/4λ

long ground-contact radials.

Under almost all conditions 40-50

straight radials, each about .2λ long,

mitigates nearly all “ground” connection loss. Improvements going to 100 radials, or using longer radials,

are

less than 1dB. Less than 1dB change is almost always unnoticeable in terms of

performance on skywave paths. For all practical purposes, we can consider 30

radials 100-feet long a nearly perfect 160-meter ground. I do have 100 buried

radials 200 feet long on my 200-foot tower, but mostly for safety and to

function as a counterpoise or reflective screen for other antennas in that

field. I realize those radials are overkill for vertical efficiency.

I’ve also found base impedance a terrible way

to judge efficiency. I’ve had systems with 60-ohm base impedances produce the same

efficiency as systems with 36-ohm base impedances. Anyone making field strength

and impedance measurements on a variety of systems will quickly learn field

strength and impedance change are not locked in step. If we want to know field

strength change, we must measure field strength.

Counterpoise Systems

Counterpoise systems are substitutes for large RF earth-based ground systems.

Counterpoises, when properly implemented, can be very effective. Counterpoises

can also be a source of frustration, providing poor lightning and safety grounds, encouraging local

RFI (radio frequency interference), and sometimes creating receiver noise ingress

problems. Other than bandwidth and lightning/safety grounding, properly

installed counterpoise and radial systems will work about the same. Good

performance is more about not doing something wrong in either system than any particular system

being special or magical.

If something is wrong with an initial system, any change can be an

improvement.

We sometimes cannot freely choose our ground or counterpoise systems. Marconi antennas or end-fed antenna systems located far from earth require

counterpoises. Such systems are sometimes described as “groundplanes” or

“elevated radials”, although by definition they are also counterpoises. Another

application better satisfied by counterpoises occurs with limited physical space, or where

terrain or obstructions prohibit an adequate buried ground system of 20-30

reasonable-length radials.

While we should do the best we can, even compromise systems are better than

no system at all.

Cautions using Counterpoises

Counterpoises and sparse radial systems, such as four-radial groundplane

antennas, operate with considerable potential between the counterpoise and

“ground”. “Earthing” the counterpoise is generally a bad idea. Earthing occurs from counterpoise wires in very close

proximity, or direct contact, with earth. Wired counterpoise to earth paths have

a similar effect, often significantly reducing counterpoise efficiency. This includes accidental

wired paths to

earth through

feed lines.

A second detrimental effect comes from creating unnecessarily concentrated

electric induction (energy

storage) and/or magnetic induction fields around the counterpoise system.

Very short counterpoises, in terms of operating wavelength, cause very high

voltages to appear between the counterpoise and surroundings, including lossy

soil. Similarly, a single thin conductor has a very high surge impedance,

because capacitance distributed along conductor length is small compared to

series inductance. The high surge impedance increases electric field intensity

by concentrating the electric field. Making matters worse, without end-loading, a short conductor

concentrates current at the counterpoise feedpoint end, concentrating the

current and magnetic field.

Concentrating any field in a smaller cross sectional area of lossy media

increases loss. Reduced field concentration is why large area (in terms

of wavelength) radial systems have less loss than small systems, and why a big

thick carbon rod with large end-plate contacts that spread fields has less loss

than the same carbon rod with point contacts concentrating fields.

Unfortunately, space limitations and local obstructions often restrict

counterpoise or radial system size. When restrictions force a small system, we

can maximize available performance. There

are three ways to reduce earth losses near a counterpoise:

*The counterpoise can be made larger, with multiple cross wires. This

allows fields to spread, rather than concentrate in lossy earth

*The counterpoise can be elevated some height above from earth. This also

allows fields to spread, rather than concentrate in lossy earth

*All earth paths, including the feed line,

must be isolated or

insulated from

the counterpoise. This prevents conducted currents from directly entering

lossy soil

We sometimes hear radials or counterpoises need only be as long as the

vertical is high. Truth is opposite this myth. Shorter

verticals generally require larger and better grounds for peak efficiency.

The sole exception to 20-30 radials “being enough” occurs more often when an

efficiently designed and properly constructed vertical antenna is very short in

terms of wavelength!

Counterpoises and Local Fields

It would be nice if we could cancel local

reactive fields. Cancelling fields, or

making small spatial antennas seem large, has been a common thread running

through magical antenna systems. The E-H antenna, Super-C antenna, CFA (crossed

field antenna), Isotron antenna, and other antennas claim to have special

properties making them work like larger antennas. The common threads woven through these designs

are special shapes, phase, reduced induction fields, or increased conductor

thickness somehow mitigates

losses associated with reduced size systems.

While there are ways to minimize

deleterious interactions, most theories are founded in junk science. For example, proponents of small magnetic loops

often claim

lack of strong electric fields makes the loop less subject to local losses and

noise. They never

researched enough to see about λ/8

from the

small magnetic loop, the electric field dominates! Nether the small electric

dipole, or the small magnetic loop, maintains the same field dominance with

distance.

There

are dozens of ways to make small antennas or grounds that “work”, with none being

magical. Rest assured, if we cancel or

eliminate any field, we no longer have an antenna or counterpoise.

The real trick is to avoid design or installation errors.

also see Verticals and Baluns page,

and longwire page

If a radial system or counterpoise system has to be small, isolate the

counterpoise from earth paths. Decouple feed line shields. This can be worth

several dB.

The feed line shield is a commonly overlooked path for common mode currents.

The feed line can provide a path connecting earth resistance across the voltage

between counterpoise and ground. There should always be a shield RF isolation

device, a proper current balun or shield isolator will work. With a balun,

balanced terminals connect to the counterpoise and antenna, just as with a

dipole. While use of the term “current balun” may seem strange, but the

counterpoise system is not perfectly balanced or perfectly unbalanced. The

current balun does the same job it does in a dipole, ensuring the counterpoise

and antenna terminal share equal and opposite currents. This isolates the

feed line shield from the antenna feed terminals.

Failing to isolate the counterpoise from earth, which includes properly

elevating and insulating the counterpoise, can result in several dB loss on

transmitting, as well as bringing unwanted RF into the shack. While insulation

is better than a bare wire lying directly on earth, wide air spacing is by far

best.

feed lines are often left out of models. This can allow creation of systems

that don’t work as well as expected in the real world. By inserting a wire

representing the coaxial cable shield path, we can see the effects of

counterpoise to earth voltage in a model.

One way to observe maximum counterpoise-to-earth voltage in a model is to

insert a source set to zero current, or a load with very high impedance, in a

wire connected from earth to the counterpoise terminal at the feedpoint.

This is a small non-resonant T system with ~40-foot ground area

radius.

In this case, with non-resonant T counterpoises, voltage across a gap in wire 14 is

5300 volts RMS with 1500 watts applied to the antenna. This illustrates the

enormous electric field between counterpoise and earth using low-density

counterpoises with perfect ground-independent sources.

If we inserted a 1000 j500 common mode impedance balun in wire 14, balun dissipation

would be 277 watts. Common mode current on feed line shield will be 0.52 amperes.

A normal good-quality balun appears inadequate for isolating this small

non-resonant counterpoise system. Even 5000-ohms balun impedance is too low.

Isolation would require a high voltage

resonant choke, parallel-tuned to 160 meters.

Projections indicate this system

should be within 1-2 dB of sixty radials 100ft long, although optimum performance

might require counterpoise heights as much as 0.1 foot above earth per meter

wavelength. A 160-meter system might require 16 feet of counterpoise height, and

that will directly subtract from effective radiator height.

If we don’t isolate the ground path in this small non-resonant radial system, as much as 5 dB

loss can occur. If you have a small untuned counterpoise on or near earth, or

connected to earth through cable shields or ground rod, most of your transmitter

power can be wasted heating the earth. Much more power can be dissipated in earth losses than

radiating!

Without loading inductors in the four 8-foot high non-resonant radials, and

with a garden variety feed line choke, we have -3.2 dBi estimated peak radiation.

It can be even worse than this, but this might be considered typical.

This is the same radial system and antenna with a perfect ground isolation

feed line choke. Radials are NOT resonant. The only thing changed was the

feed line choke.

Resonance does not directly help the radials or antenna work better. Radials

greatly reduce the voltage from counterpoise common point to “earth”, and this

makes decoupling the feeder much easier.

Look at the plot below, where radials are made resonant. Field strength is

the same.

|

Out-of-resonance radials will also modify the resonant frequency of

the antenna system. Radial reactance is in series with the antenna feed.

Unless the feed line has considerable common mode currents on the shield

outside, adding reactance on the counterpoise side by mistuning the

counterpoise changes resonance and SWR just as mistuning the antenna

does. Mistuned radials will not only stress any feed line choke or cause

RFI, mistuned radials will also shift system resonance.

|

Adding 600-ohm reactance loading inductors in each radial wire at the feedpoint, and tuning for minimum counterpoise-to-earth feedpoint voltage, reduces 1500-watt counterpoise feedpoint voltage from

5300 volts to just 36 volts. Unfortunately, the

voltage null only holds over a small frequency range.

In this case, near radial resonant frequency, almost any balun or isolator will work. Running elevated radials

or counterpoises out of resonance is clearly a very bad idea, yet this is

exactly what many installations, including some manufactured systems, do.

Resonating the counterpoise, if it is a small counterpoise, significantly

reduces common mode problems.

Loading the radials at the T-junction improves field strength slightly, and

makes the antenna less sensitive to ground type below the antenna and

counterpoise height. This is a not a major increase with this particular example

of height and earth

type, although there are cases where improvement can be greater.

This is the same antenna with 40 radials 100-feet long.

Should people be amazed small ground systems work well when properly

installed? When we do a system properly, even a half-size system (40-foot radius in this

case) works OK.

The primary advantages of large systems are increased immunity to lightning,

reduced common mode on

feed lines, and much wider operating bandwidth. Large systems are less sensitive to ground

contact, more repeatable, less dangerous (lower voltages and field levels), and require less maintenance.

Resonate the Counterpoise

Resonating the counterpoise reduces counterpoise feedpoint-to-earth voltage.

This reduces common mode on the feed line, and relaxes current balun or choke

requirements.

One way to resonate the counterpoise is to measure counterpoise to earth

voltage at the counterpoise center, and adjust for minimum voltage.

A second way to tune the counterpoise is to disconnect it from the antenna,

and feed it like a low dipole. Adjust it for resonance.

Frequency Sensitivity

Multiband systems present a unique problem. The counterpoise or radial system

ideally must present a low common mode impedance across every operating band.

This is an extremely difficult goal if multiple bands are present.

Frequency sensitivity of a counterpoise can be modeled by placing the

counterpoise a few feet above a perfect ground, inserting a source in series

with a 50-ohm load in a short very-thick vertical wire, and attaching the

counterpoise to the top. By making a 50-ohm SWR sweep, a graphical

representation of low and high common mode impedances appears. The vertical wire

slightly skews frequency lower, but overall we get a good idea of frequency

sensitivity and problem bands.

Care must be exercised looking at the results. Reactance is not quite as much

problem as high resistance, because reactance can be “compensated out” with

changes in antenna tuning. High resistance will increase feed impedance

regardless of antenna length corrections or compensations, but will NOT

necessarily increase system loss. High SWR indicates bands or ranges where

feed line common mode or stress on feed line chokes will be problematic.

Here is a 1.8-30 MHz sweep of a 50-ft long single-wire counterpoise:

This plot shows a low common mode impedance at 4.8, 14.4, and 23.8 MHz. This

was roughly expected, based on length.

Making a four radial-wire counterpoise with 50-foot legs, we have:

We can see noticeable broadening of SWR nulls, and a slight downward

shift in frequency (mostly due to the vertical wire). Look at the following

systems:

Thirty 50ft radials:

Thirty 50ft elevated radials are bad only in the area of 10.8 and 21 MHz.

Sixty 50ft radials:

Interlaced 50 and 25 foot radials

We now have two more sweet spots, and have further narrowed bad areas:

We sometimes get surprising results. If we make the longer radials 60

feet, and the shorter radials 30 feet, we might assume we have fundamental 1/4λ

coverage of 80 and 40 meters, as well as

odd-harmonic coverage of the basic radial frequencies. We really have

this plot:

We have reasonable 80, 40, 15, 12, and 10 meters response, but no 20 meter

coverage, although the system is usable on most bands if we choke the feed line

and tune the antenna to correct reactance. The system is not terribly bad on 160

meters.

What happens if we make the same 60 and 30 foot radials close together, with

2 foot open-end spacing?

We now lose 15 meters. This is because the radials act like open stubs, and

detune 15 meters. We still have six nulls, but move and sharpen tuning and lose

some bands.

So how do we cover multiple bands? It looks pretty difficult without a large

screen or earth contact radials, unless we fiddle around until we move any

impedance bumps out of band.

Cover Largest Spatial Area Possible

More linear spatial area spreads counterpoise voltage (electric field) and

current (magnetic field).

Parallel Antenna’s Horizontal Element Areas

With antennas like T’s or L’s, orient a counterpoise parallel and directly

below horizontal antenna wires.

Various Configurations

T

Z or L

Y

X

Screen

Inductor Loaded

Folded or Stub Loaded

|